Today, we are going to talk about how insurance companies make money and how they reduce losses.

You thought this was a blog on options investing.

And it is.

It turns out that there are a lot of parallels between selling options and selling insurance.

Contents

Options As A Form Of Insurance

Options can be thought of as a form of insurance.

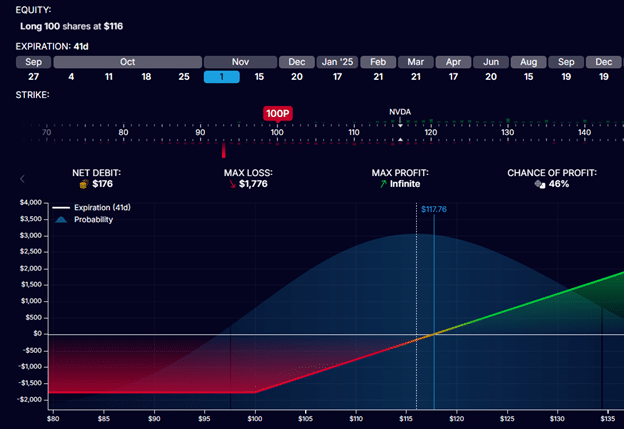

Suppose an investor purchased 100 Nvidia (NVDA) shares at $116 per share.

The investor is fine holding the stock as long as it does not drop below $100 per share, which is the recent swing low of the stock.

He does not want his investment to lose more than $16 per share.

Therefore, he purchased one put option contract on NVDA with a strike price of $100 and an expiry of 41 days out.

The put options contract grants him the right to sell 100 shares of NVDA at $100 per share, provided that he exercises this right on or before the option expires.

This right guarantees that he would not lose more than $16 per share from the stock even though the stock might drop way below $100 per share.

This contractual right is only valid if the option contract has not expired.

The put option contract is a form of insurance.

Like all insurance, the purchaser must pay money to buy it.

This cost is called the premium.

In this case, the put option costs $176 per contract.

While he may not lose more than $16 per share from the stock sale, the cost of the put option must be considered when determining the maximum potential loss of the investment.

In the worst-case scenario, when NVDA is below $100 per share at option expiration, he loses $1600 from the stock sale plus the contract cost ($176).

So, there is a maximum investment loss of $1776.

The risk graph of the NVDA option looks like the following for an investor who has purchased 100 shares of NVDA and one contract of a $100-strike put option expiring on November 1st:

Source: OptionStrat.com

If the NVDA stock price soars above $100 per share, the put option holder’s right to sell the stock is not used.

He keeps the stock, and no harm, no foul.

Remember that he loses the $176 he paid to purchase this option contract.

Insurance Sellers

Insurance companies are in the business of selling insurance.

The premium that they collect from the sale is their revenue coming in.

The insurance purchaser is willing to pay this premium to the insurance company so that the insurance company can take on the risk of an adverse event.

We pay a premium to buy car insurance so that we are not on the hook for expensive car repairs when we get into a car accident.

The insurance company takes on this risk and pays for these expensive repairs.

As long as the insurance company collects more money in premiums than the cost of the repairs and other administrative/business costs, then the insurance company makes money.

Options Sellers

Option sellers are in the business of selling option contracts.

In our example, the option seller collected $176 from the sale of that one put contract.

If the NVDA price is above $100 per share at option expiration, all is good for the option seller.

They keep the premium and profits at $176.

They take on the risk of the stock dropping below $100 per share.

Say that NVDA is at $90 per share at expiration; the option seller is obligated to buy 100 shares of the stock at $100 per share.

Therefore, they lost $10 per share, or $1000 for 100 shares. Since they did collect $176 for selling the contract, they lost $824, which is $1000 – $176.

The risk graph from the option seller’s point of view is:

How Sellers Make Money

To increase the likelihood of the insurance companies and the option sellers to be able to stay in business and be profitable, they:

- Diversify their risk

- Be selective about who they sell to

- Collect enough premium for the risk

- Cap their max loss

Diversify The Risk

The car insurance company doesn’t want to sell to just ten drivers.

The ten drivers might all turn out to be bad drivers and crash their cars.

The car insurance company wants to sell to hundreds of thousands of drivers – some bad, some good, and mostly average drivers.

This spreads out the risk so that not everyone gets into car accidents – or at least not simultaneously.

House insurance companies don’t want to sell only to houses in the tornado zone.

One tornado could lead to a large loss.

They want to sell insurance across a wide geographical area so that a single act of nature (such as a wildfire burning down a select geographical area of houses) would affect only a small percentage of their policies.

Similarly, option sellers may try to diversify their risk by selling across different assets, option strikes, and option expirations.

Be Selective

Some home insurance companies may not want to sell insurance to those in earthquake zones.

Some health insurance companies may not want to sell insurance to the elderly or people with pre-existing health conditions.

They may not want to sell to high-risk members but might have to do so due to ethics or by law.

Collect Enough Premium

In those high-risk cases, they will charge a higher premium to make sure that they are paid for the amount of risk they take.

Insurance companies employ actuaries who use statistics and probabilities to calculate risk and determine the premiums to collect to offset this risk.

Option sellers also need to ensure they are collecting enough credit for the risk in the trade. They may calculate the risk-to-reward ratio.

Cap Their Max Loss

Some long-term care insurance companies (or other insurance companies, for that matter) may have a clause that says that the maximum payout throughout a lifetime is, say, a million dollars.

Members who want a greater maximum payout cap may have to pay larger premiums.

This is how insurance companies cap their loss against a potential catastrophic loss.

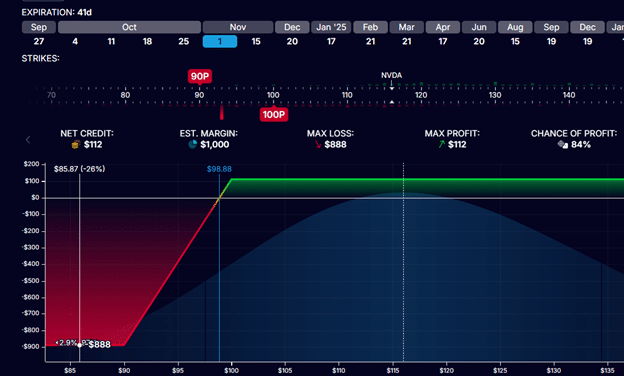

Options sellers who sold a put option may purchase another put option (at a lower strike) to cap their loss as well.

Suppose the $90-strike put option costs $64 per contract.

Then, the risk graph of a sale of the $100-strike put option along with the purchase of a $90-strike put option would look like this:

This is a credit spread.

This caps the maximum risk of the trade to $888.

In the worst-case scenario where NVDA is below $90 at option expiration, the option seller has to buy 100 shares at $100 per share.

He can also sell 100 shares of NVDA at $90 per share due to rights granted to him by the purchased $90-strike put option.

Buy at $100 and sell at $90 means a loss of $10 per share. With 100 shares, the option seller would lose $1000 minus the credit collected initially.

The credit collected initially is $112.

This is calculated from the sale of the $100-put (received $176) and the purchase of the $90-put (costs $64)

So, max loss of the credit spread is capped at:

$1000 – $112 = $888

Conclusion

Selling insurance and selling options have a lot of similarities, as both involve collecting premiums in exchange for taking on risk.

Insurance companies promise to compensate policyholders in the event of a specific loss or disaster.

Sellers of put options take on the obligation to buy an underlying asset at a specified price if certain conditions are met.

Sellers of call options take on obligations as well.

However, this article did not delve into call options for brevity.

Both insurance companies and options selling can be profitable because long-term statistics are in their favor if probability forecasts are accurate and risks are properly managed.

However, neither business comes with a guarantee of steady profits.

Because life, natural events, and the market can sometimes be unpredictable and can produce rare and unforeseen events.

This is known as a “black swan event.”

We hope you enjoyed this article about how insurance companies make money.

If you have any questions, please send an email or leave a comment below.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.