The basic building block that all option traders learn is the two vertical spreads: the credit spread and the debit spread.

Contents

The credit spread is a favorite among option sellers, especially the beloved bull put credit spread.

And we love them too – especially when the market goes up most of the time, and the bull puts credit spread and collects premiums into our accounts.

But is that a reason to completely ignore, or downright hate, the debit spread?

I recently heard a trader say “death before debit” and said that it meant that he would “rather die than pay a debit for a trade.”

Obviously, he says that in jest.

But if you follow his work, you will find that he puts on complex options structures that are net short options and collects a net credit.

For example, broken wing butterflies and ratio spreads.

Even if he trades directionally and has to buy a bull call spread, he would sell a larger bull put credit spread to collect a net credit.

(This is what is known as a risk reversal trade).

He wouldn’t be caught dead doing a calendar because calendars are always a debit transaction.

So if a debit spread walks into a bar and the host says to it, “Death before debit,” it would be insulted and walk out.

Today, we are going to give the debit spread some love

No room for hate here.

All option structures are welcome.

The Bullish Debit Spread

Since a lot of options investors are familiar with buying a call option when the underlying price is expected to go up, we will start with the bull call debit spread.

We buy a call option, which will be our primary profit generator if the price of the underlying moves up.

But we also sell a call option to collect some premiums and reduce the net cost of our trade.

For example:

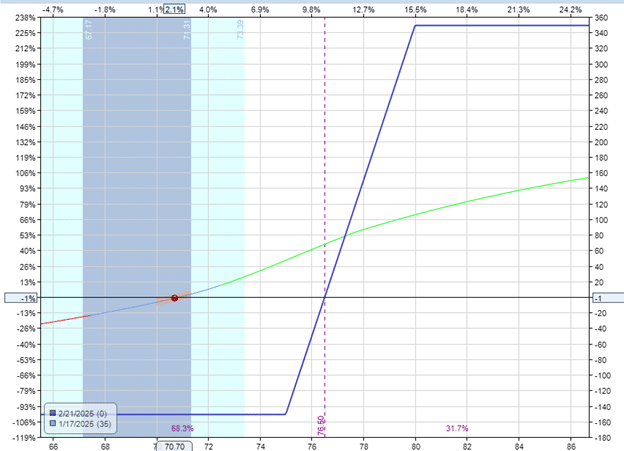

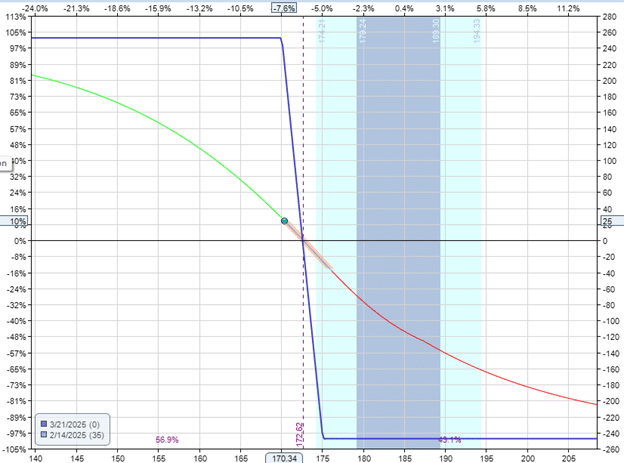

On Jan 17, 2025, Palantir (PLTR) is trading at $70.70; the investor buys the $75/$80 call debit spread expiring Feb 21 (with 35 days till expiration).

Date: Jan 17, 2025

Price: PLTR @ $70.70

Buy one $75 Feb 21st PLTR $75 call @ $4.58

Sell one $80 Feb 21st PLTR $80 call @ $3.07

Net debit: $151

In a debit spread, the maximum loss in the trade is the debit paid initially.

As we can see from the right-axis dollar amounts of the expiration risk graph, the maximum loss that we can have is $151 even if the market crashes and/or the stock price goes to zero:

Source: OptionNet Explorer

But if the price goes up as expected, then there is a potential to make up to $349.

This number is obtained by taking the width of the spread minus the initial debit:

$500 – $151 = $349

This is a favorable risk-to-reward ratio of one-to-two, where we are risking $1 to potentially make $2.

In contrast, many credit spreads have a risk-to-reward ratio of risking $4 to make $1, or some as extreme as risking $9 to make $1.

The Greeks Of The Debit Spread

This debit spread indeed has a slightly negative theta, which is a disadvantage compared to the credit spread.

The Greeks of the trade:

Delta: 7.41

Vega: 0.69

Theta: -0.49

Gamma: 1.21

However, once the debit spread starts winning (in this case, 5 days into the trade), the theta becomes positive:

Delta: 9.96

Vega: 0.04

Theta: 0.17

Gamma: 0.86

The low vega also shows that the debit spread is not sensitive to volatility changes (whereas the credit spread is more sensitive to implied volatilities).

Many beginner debit spread traders will be less concerned with the Greeks.

The debit spread is a directional spread.

So, the primary concern is to get the direction correct.

When we get the direction correct, the negative theta and the other Greeks are of lesser concern.

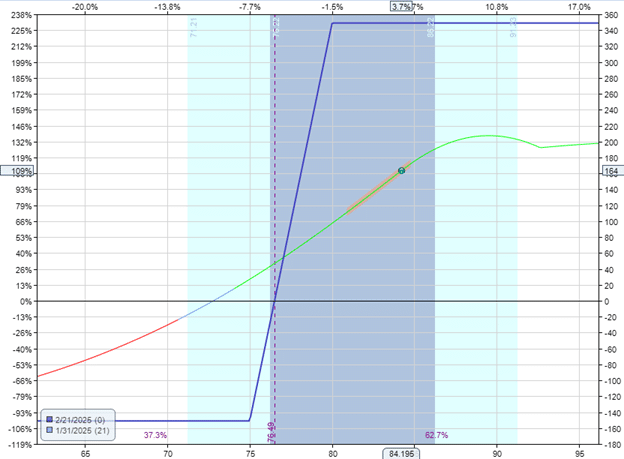

In this example, after two weeks, the trade made $164, which is more than the capital at risk.

It is around 50% of the max profit potential of the trade.

Some traders may be inclined to take the profit at this point.

If they can consistently make more than their max risk, then even getting only 50% of the trades correct can give them a positive expectancy.

The Bearish Debit Spread

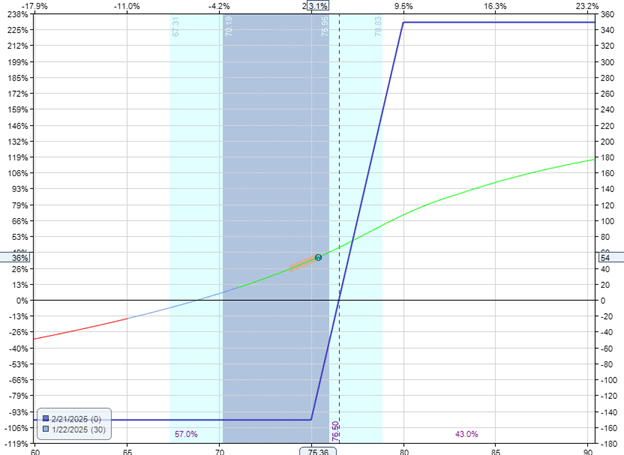

In this bearish debit spread (aka bear put spread) example, we buy an at-the-money put option, which is the main profit generator when the price of the stock goes down.

Then, we sell a further out-of-the-money put in order to reduce the cost of the long put.

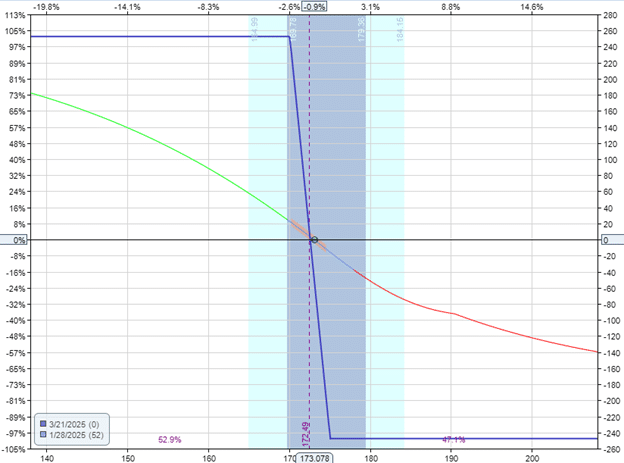

Here is an example from Applied Materials (AMAT) that is 52 days till expiration.

Date: Jan 28, 2025

Price: AMAT @ $173.08

Buy one Mar 21st AMAT $175 put @ $11.50

Sell one Mar 21st AMAT $170 put @ $9.02

Debit: -$248

Here, the risk-to-reward is one-to-one with a max risk of about $250 and max potential profit of $250.

The theta and vega are near zero.

Delta: -7.78

Vega: 0.49

Theta: -0.09

Gamma: -0.13

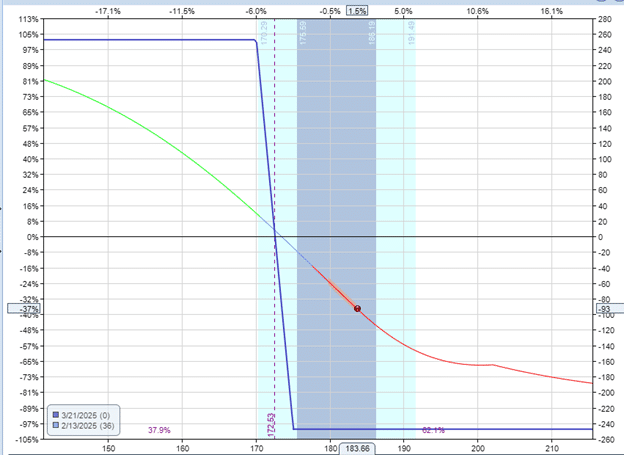

This example is where the price did not go in our favor.

Near the end of the day on Feb 13, the trade was down -$93 because the price of AMAT had gone up to $183.66.

Applied Materials has an earning announcement after the market closes on that same day.

Should the investor hold the trade and see if the earnings cause the stock to drop back down?

If the stock gaps decrease by 10 points, the trade will return to profitability, making up the $93 loss.

If the stock gaps up by 10 points, the trade will lose another 60 dollars.

This is according to the theoretical modeling of the T+0 line shown in OptionNet Explorer.

Note the asymmetric reward to risk.

If the price goes in our favor, we gain $93.

If not, we only lose $60.

The investor takes the gambles and sets a good-till-cancel (GTC) order to exit the trade for a credit of $250, which will recover the initial $248 debit paid for the spread.

The next day, the stock dropped 10 points, and the GTC order was triggered, leaving the trade break even.

Can Debit Spreads Be Held To Expiration?

Yes, they can.

And it is not dangerous to do so.

You still can not lose more than the initial debit paid.

Alternatively, if desired, the trader could not have set any GTC order and held the spread longer – even till expiration.

If AMAT is above $175 at expiration, both put options expire worthless.

If AMAT is below $170 at expiration, the spread is in full profit of $250.

The short $170 put would obligate us to buy 100 shares at $170.

But then the long $175 enables us to sell that 100 shares at $175.

In the end, we have no shares; we just have a credit of $500 in our accounts.

Considering that we paid $248 for the spread, that would be a net profit of $252.

If the AMAT price is between $170 and $175 at expiration, we will not be assigned any stock because it is above the short strike of $170.

Final Thoughts

Think of the debit spread as buying a long option.

Buy call option if bullish.

Buy put option if bearish.

At the same time, sell an opposing option to form a spread.

This enhances the trade with some advantageous properties.

The debit spread is superior to the single long option because it reduces the risk in the trade, reduces the amount of theta decay, and reduces the sensitivity to volatility.

Like the single long option, the debit spread has a defined risk: the initial debit paid.

If this risk is small enough, it can stop losses in the trade.

In contrast, the out-of-the-money credit spread has a large risk in relation to the potential profit.

Hence, credit spread traders often have to keep a mental stop loss in mind and rely on mental discipline to execute this exit.

Sometimes, the stock’s overnight gap can cause the loss to be greater than the stop loss.

Slippage in a fast-moving market against the trade can cause a loss that exceeds the intended stop loss.

The debit spread does not have this problem.

Regardless of market gaps, slippage, or lapse in trader discipline, the trade can not lose more than its initial debit – except for trader error.

The debit spread is “small account friendly.”

That means investors with small accounts can use debit spreads to put very little capital at risk.

Yet, the trade can return a 100% yield on the capital at risk.

In the Palantir bull call spread example, the trade made $164 while risking only $151.

There is no reason to kick the debit spread out of your options toolkit.

You just have to understand where its strengths are and apply them when they are applicable.

We hope you enjoyed this article on the debit spread.

If you have any questions, send an email or leave a comment below.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.