Today we’re looking at front running. What is it? How is it done? And how does payment for order flow (PFOF) fit into the equation?

Contents

- The Good, The Bad, The Illegal

- Case Closed?

- The Gray Area

- Paying For Order Flow

- Isn’t This Illegal?

- SOSDD?

- The “Right” Way to Front Run

- An Easier (and Free) Method of Front Running

- News (Including Earnings)

- The Conclusion

The year was 1928. Wall Street brokerage houses were booming.

Everybody who was anybody had a friend who was either a broker or an investor on Wall Street.

Telephones were fairly commonplace, and reading the tape looking for that next big winner was the most popular pastime for those “in the know”.

Once you found the next “horse”, you would call your broker to have him buy shares of that company.

Occasionally, if the broker was too excited or hard-of-hearing, another broker on the floor might overhear the large order, then hurriedly scratch an order down for himself.

He would then run to the trade desk to try getting his order filled before that large order came through and most certainly increased the stock price.

He had just front-run the stock.

Modern Front Running

Nowadays in the age of computers, paper orders being walked (or run) to a trade desk are a thing of the past, but the idea of taking a piece of news that wasn’t public and trying to capitalize on it is something that still goes on.

And the term front running still implies the idea of trying to make use of information before it’s fully public.

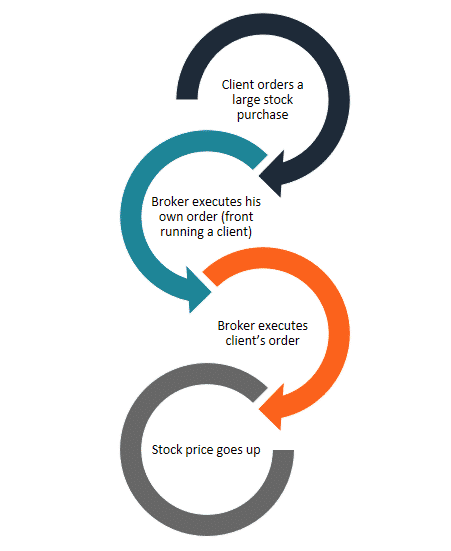

Image Credit: Corporate Finance Institute

The Good, The Bad, The Illegal

In and of itself, trying to make use of information before “the world” joins in, is at the heart of a capitalistic society.

Discovering a new diet that sheds pounds faster and safer than other diets and trying to make money from that isn’t wrong.

But, if you’re working for a research firm charged with determining the efficacy of this diet and then you break off to try releasing your own version of the diet before the other one finishes its trials, you’re no longer “in the right”.

In many ways, front-running is akin to insider trading.

The only real distinction is that with insider trading, the person with the knowledge works for/owns the company.

In front running, it’s the broker who has the information and tries to profit from that knowledge before placing the client’s order.

Or, as in the diet example, it could be a stock analyst who is about to issue (for instance) a strong buy recommendation for a company, but decides to buy some shares before releasing the recommendation.

And yes, as you might well imagine, such front running is illegal.

Case Closed?

If front running is illegal, why are we talking about it?

Well, not so fast. From an analyst’s, or a broker’s or an insider’s standpoint, front running is illegal.

There are, however, certain circumstances that are gray areas, deemed technically legal.

And there are other circumstances that qualify as fully legal.

The Gray Area

Let’s say that you’re the analyst.

You have just determined that stock XYZ has superb fundamentals and based on other technical analysis, the stock is at a very good buy point.

You are about to issue a “Strong Buy” recommendation to the public, but before you do, you buy some shares for yourself. Up to this point, what you’ve done is illegal.

However, now when you make the recommendation, you fully disclose that you have purchased shares in XYZ before stating the reasons for your “Strong Buy” recommendation.

Because you have disclosed that you stand to make a profit on the increase of stock XYZ before you make the actual recommendation, it technically is “legal”.

I’m not here to (nor am I going to) debate whether I agree with that or not.

As of right now, it is what it is, and it’s been deemed legal.

Paying For Order Flow

Another gray area involves the practice of Pay For Order Flow (PFOF), most commonly done by high-frequency trading (HFT) firms.

To unpack this, let’s go back to the original form of front running…

Instead of a singular broker trying to make a run in front of a large order, the PFOF model is akin to the brokerage firm taking all the slips with orders (the order flow) and collecting them in an effort to sell those orders to another firm.

This other [HFT] firm then gets to “look at” those orders and decide if it’s going to make a market for those trades (that is, take the other side) or pass them on to another brokerage.

Why would that make a difference?

In broad terms, institutional orders (also called “smart money”) are usually in the high figures, hundreds of thousands to millions per trade.

Retail orders, those made by the general public (also called “dumb money”), are usually for considerably smaller amounts.

Retail traders are likely less informed than institutional traders, and since institutions are the ones actually “moving” the market (because of their large trade sizes), HFT firms can easily distinguish between the two types of orders, decide where the smart money is going, and then take the opposite side of any retail trades going against the smart money.

That was a lot to process, so let me clarify some: BIG trades in one direction and SMALL trades in the opposite direction.

HFT firms see both orders (because of PFOF), so they know it’s a relatively “safe bet” to create the market for those small trades.

The small trades are going against the smart money, so if they go against them, they’re placing trades on the same side as the smart money.

It’s like this: the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Isn’t This Illegal?

You may think so, but no.

They don’t know who the orders are coming from, even if they have a good “general sense” of what kind of trader it is.

They are giving a “good price” for the spread, which makes the retail trader happy, and they make a profit when the trade moves in the direction the institutions want, so they’re happy.

If, on the off chance, the trade goes against them, it’s for the small amounts of those trades.

In other words, the HFT firms are acting like the “house” of a casino.

The odds are high that the trades they are making the market for are the retail traders.

Retail traders don’t win that often.

In the long run, the few losing trades the HFT firms take are nothing compared to the overwhelming majority of trades that are winners.

The house always wins [in the long run]. It’s the “whales” that they have to keep their eye on to make sure they don’t lose too much.

avoiding the large trades, HFT firms can essentially avoid the “whales”, keeping their winning percentage (and in turn, profits) incredibly high.

SOSDD?

Is this just the same old story on a different day?

There’s no question that the two are very similar.

There are some rules and regulations that require brokerages to disclose the practice of PFOF.

Notably, this is what put Robinhood in some hot water recently as they failed to disclose this on their “How Do We Make Money?” page.

What makes PFOF legal is again tied up in disclosing what you are doing up front. But “terms and exclusions” on car ads are also required.

As are “known side effects” on prescription drugs.

Yet where is all of this information typically found?

In super small, you-need-a-microscope-to-read-it, fine print.

And who reads that stuff, anyway?

Maybe you, after reading this.

The “Right” Way to Front Run

What makes most front running “wrong” is the fact that the person has “hidden” (non-public) information that most certainly would impact a stock’s price, and they’re using that information for themselves before it’s public.

But what if there was a way to use public information to try to get a jump on a move in a stock?

In fact, there are many ways of possibly doing that.

One way is by tracking market depth and trying to compile reasons why a particular stock might go up (or down).

Market depth, also sometimes referred to as Level II Market Data or the order book, shows more detail in terms of number of shares being offered at a specific price, whether they have been filled or are waiting to be filled.

This information is public inasmuch as anyone who wants to can have it, though it isn’t always free.

An Easier (and Free) Method Of Front Running

There are many ways of tracking the stock market, but one of the most common ways is by looking at or following an index.

Three of the most popular indexes are the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ Composite Index.

An index is nothing more than a hypothetical portfolio intended to show a particular segment of the market.

There isn’t a way to “own” a particular index; however, there are funds that have been created to mimic the behavior (movement) of those indices.

As such, when a particular stock is added to (or removed from) an index, the corresponding fund(s) will need to add (buy) shares of that company, or possibly subtract (sell) shares of that company.

Also, certain indexes are weighted, so if a particular stock really overperforms or underperforms, the fund may need to adjust its holdings to better match the index.

As a result, you can “predict” what will happen – at least short term – to a given stock’s price.

Index funds are not always able to act the same day an announcement is made, so there is a “lag” between the time the index announces the change and when the funds can adjust their holdings accordingly.

This gives the savvy investor time to get in to (or out of) a particular stock before the funds make their adjustments.

News (Including Earnings)

Another potential way to front run is based off of news.

This isn’t generally as predictable, but oftentimes, if a company is getting offered to be bought, their stock price will rise as a result.

Or if, say, a pharmaceutical company announces favorable drug trials, their stock often rises (at least in the short term).

Earnings are another form of news, but are often the most difficult to predict when it comes to how the stock will react.

Stocks don’t always react to news (and especially earnings) in a predictable manner, so you should exercise caution if basing your trades off of news or earnings.

Conclusion

Front running has many different faces, not all of which are positive.

The main distinction comes down to how the information was obtained, and whether or not it’s available to the public at the time the trade was made.

If it’s public, there’s no harm trying to “beat the crowd”.

If it isn’t public, or if you are in a position where you are acting on behalf of a client – and place a personal trade before the client’s – then you have exited the freeway and are travelling along illegal highways.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.