There is a good chance that every person will live through one or more large economic bubbles at least once in their lives.

As these are relatively infrequent events, often people are caught unaware that a bubble is forming and as a result are surprised by the speed and ferocity with which prices come crashing down.

Prices of assets in an economic bubble can rise to astronomical levels before crashing 60%, 70%, or even 80% or more, wiping out all an investor’s gains and even leaving them bankrupt.

The devastating effects of these bubbles mean that every investor should be aware of how they’re formed and how they play out so that they can prepare and protect themselves against the eventual bust.

Since most investors will only encounter relatively few bubbles in their lifetime (and not always in the asset they’re investing in), we need to take a look back throughout history for examples we can learn from.

This article will explore economic bubbles that have occurred in history, covering how they were formed, how they burst, and what the eventual impact was.

Before we go into the examples, it is worth exploring the common patterns of an economic bubble – while every economic bubble is a little different, they all follow a relatively similar chain of events.

Contents

- How Economic Bubbles Form

- The Tulip Mania of 1636 – 1637

- The Mississippi Bubble of 1719 – 1720

- The South Sea Bubble of 1720

- The Roaring Twenties 1924 – 1929

- The Japanese Bubble of 1984 – 1989

- The Dot Com Bubble of 1990 – 2000

- Conclusion

How Economic Bubbles Form

The beauty of reviewing past economic bubbles is that you can tease out the commonalities and patterns so that you know the warning signs.

Bubbles generally go through five stages:

Stage 1

In the first stage, there is a product or asset with some level of scarcity that is traded amongst individuals, corporations, and/or countries.

It doesn’t matter what the product or asset is, it could be traditionally valuable items like stocks, bonds and property, through to non-traditional and even mundane sources of wealth like a flower.

During stage 1, as investor expectations begin to divorce themselves from rational analysis, the price of the asset begins to rise above what the fundamentals would reasonably imply would be ‘fair value’.

This can be caused by any number of factors, such as unreasonable projections of past results into the future, overly optimistic analysis, increasing popularity amongst amateur or ill-informed investors, and complacency after years of easy returns.

Stage 2

During stage 2 a very large upswing in prices occurs, which are not supported by fundamentals.

Prices rise to unrealistic heights as a result of a self-fulfilling feedback loop.

Bolstered by recent price rises, investors expect the price rises to continue so they buy more.

This added buying pushes prices up again, attracting further buying.

At the same time, people who normally would have sold end up holding onto the asset hoping to sell it for more later on.

This simultaneous withdrawal of sellers, combined with more and more investors piling in pushes prices up further until even non-investors start to wade in, hoping to earn easy money.

Stage 3

In stage 3, the bubble pops.

Often this is in response to some sort of triggering event, such as actions by regulators, an easing in supply constraints or analysis showing further profits are impossible.

Sometimes it can be as simple as the psychology of market participants shifting from greed to fear.

During this stage, the relentless upswing in process is arrested and selling begins to increase, pushing down prices.

Stage 4

Stage 4 acts with a similar self-fulfilling feedback loop to stage 2, except that it happens in reverse.

After the bubble pops and prices have already begun falling, investors begin to lock in profits and start selling.

Since the price is inflated well above even the most optimistic fundamental analysis based valuations, and most people have bought in already, there are few buyers available.

This requires sellers to drop prices further, kicking off the feedback loop as more people start to lock in profits and sell when there is insufficient buyer appetite.

Pretty soon the falling prices mean everyone clamors to exit and sell their position, resulting in a final capitulation and crash.

Stage 5

Prices plummet to zero or extreme bargain prices as the asset falls out of favor with investors.

During the final stage, bankruptcies of individuals, companies and even countries occur as the rapidly falling asset prices expose over-indebted entities.

Now that you understand the basic stages of an economic bubble, you’ll be able to spot this playing out in the historic examples that follow.

The Tulip Mania of 1636 – 1637

Of all the economic bubbles in history, none captures the fascination of so many people as the Tulip Mania of 1636 to 1637 as it was one of the greatest bubbles in history and it was centered on nothing but a humble flower.

The tulip was introduced to Western Europe in the mid-16th century and became highly desired amongst the wealthy elite of Holland.

The wealthy Dutch collectors designed tulip classifications based on characteristics like color and species.

These classifications created a hierarchy of tulips, with some more desirable, and therefore more valuable, than others.

Since it was impossible to know how a bulb would flower, the wealthy elites began to use tulip bulbs for speculation.

As this new-found hobby of the elites took off, more and more people became involved.

Soon it spread to commoners and the surge in demand caused the price of the bulbs to soar.

People became so fixated on speculation that they began to mortgage their homes and business in order to buy more bulbs.

This frenzy of buying pushed prices up to astronomical levels by late 1636.

However, in early 1637 consumer appetite for paying the high price for tulips suddenly evaporated.

The market crashed suddenly and sharply and prices collapsed to pre-bubble levels.

Nobody was willing to buy tulips and many people found themselves in possession of worthless flowers, resulting in the government stepping in in late May of 1638 to allow tulip contracts to be annulled upon the payment of 3.5% of the initially agreed-upon price.

The Mississippi Bubble of 1719 – 1720

In 1715, Louis XIV of France passed away at a time when the French economy was in a dire state.

The value of its’ metallic currency was unstable, fluctuating wildly on a regular basis.

In an effort to improve financial stability, the Banque Royale began to issue banknotes payable in the value of any metallic currency that was deposited (i.e. paper money).

The scheme was successful and the man who first came up with the idea (John Law) saw his fame and power rise.

Leveraging his newfound fame and power, John Law set up the Mississippi company in 1717, which had a monopoly on trading rights with French colonies.

As the wealth and power of the company rose, in 1717 it subsumed the entire French national debt, allowing it to be exchanged for shares in the company.

As there were more investors available than shares on offer, demand for the shares rose strongly and the Banque Royal printed further paper currency in response.

In 1720 there was a run on the Banque Royale which did not have enough metallic money to cover even half of the paper money in circulation.

The government intervened to depreciate Mississippi company shares, however public outcry caused them to reverse this decision just one week later.

Regardless, the Banque Royale stopped payment in specie and the bank runs continued until the Mississippi company shares became worthless six months after the first bank run had started.

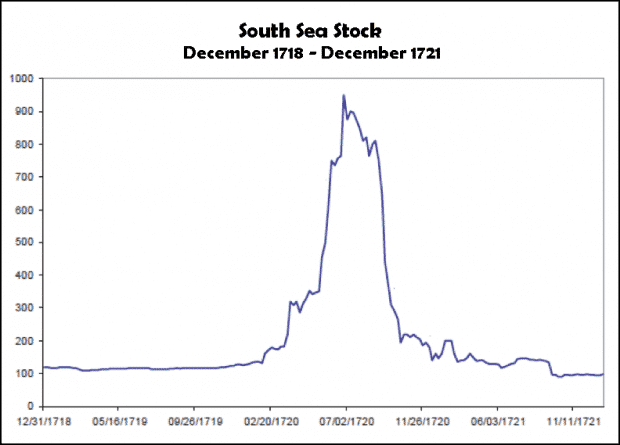

The South Sea Bubble of 1720

The South Sea Bubble occurred around the same time as the Mississippi Bubble and for strikingly similar reasons.

In 1711, the English government was heavily indebted due to wartime spending.

A company named the South Sea Company was created which converted 10 million pounds of government debt into its own shares.

Source: investorvillage.com

Source: investorvillage.com

As a reward for this, the government allowed the South Sea Company to have a monopoly on trade with both South America and the South Seas.

Further, the government also decided to issue the South Sea Company with annual interest payments.

This made the company an attractive prospect for investors and when they saw the success of the Mississippi company in France in 1720, they decided to follow a similar approach and take over the entire British national debt.

Shares in the company sold out very quickly during the first offering to the public, spurring subsequent offerings which also sold out.

The stunning success of the multiple capital raisings by the South Sea Company meant that it attracted many outlandish and at times, outright fraudulent companies being formed.

This led to the Government enacting a law requiring government permission to enact a new company and that the company may only enact activities as listed in the company’s charter.

By August of 1720, investors and foreigners, concerned with the rapid ascent of the stock price (more than 3 times the initial offering) started to cash in their bets and withdraw from the market.

This precipitated a sharp and sustained fall, which ultimately resulted in the price collapsing by 75 percent in just four weeks and the arrest of corrupt politicians and businessmen involved in the scheme.

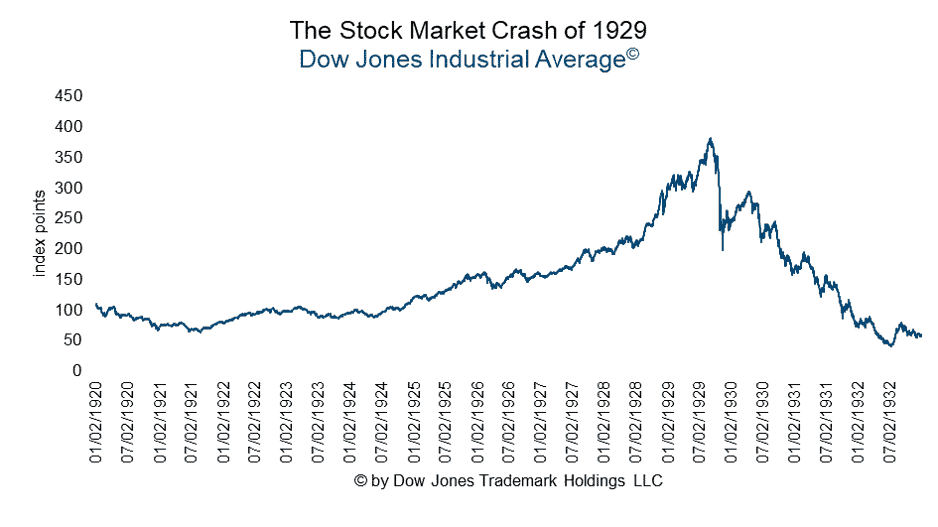

The Roaring Twenties 1924 – 1929

Most people have heard about the Great Depression which caused untold misery and suffering for millions of Americans and many others around the world.

However, fewer people realize that in the decade before it, America was experiencing one of the greatest bull markets in history.

The early 1920s saw a period of growing prosperity for America as it sold an increasing amount of goods to ravaged European economies that were trying to rebuild following World War 1.

Economic stability, increasing prosperity, and rising stock prices encouraged more and more people to invest in the stock market, drawing in more people as the market reached ever higher.

By the mid-1920s, the markets were roaring – not because of any significant change to company fundamentals, but due to the self-fulfilling cycle of increasing prices drawing in new participants along with the addition of leverage.

As the stock market soared, an increasing number of people started to invest on margin, sometimes using so much leverage that they had cash to cover as little as 10-30% of the stocks they owned.

Brokers were only too happy to oblige millions of eager individuals to take on more highly-profitable leverage as it was seen as a win-win for both brokers and investors.

By late 1929 stocks started to go down as investors became rattled by ever-increasing bad economic news.

The highly leveraged positions led to an avalanche of price falls, and over the course of several years, the stock market crashed a stunning 89%.

The Japanese Bubble of 1984 – 1989

In the lead up to the 1980s, on the back of a booming, post-war, high tech manufacturing economy, Japan enjoyed one of the highest economic growth rates in the world.

The seeds of the bubble were sown in the 1970s as the success of the economy led the government to begin deregulating financial markets.

Firms were eventually able to start speculating in markets themselves, buying stock, and reporting it as earnings on balance sheets.

This naturally pushed up corporate profits, encouraging more investors to buy into the company.

During the mid-1980s, the government enacted a looser monetary policy stance, lowering interest rates and expanding the monetary supply.

This meant that corporations had access to cheap capital which they then used to fund even more speculation, dramatically boosting profits and attracting more investors.

In many of Japan’s largest businesses, it was not unusual to see more than 50% of the total reported profits dominated by speculative activities.

The success of the market, combined with low borrowing rates, led to increased investor speculation in land and skyrocketing prices.

The Japanese government, concerned with the soaring stock market and property prices decided to shift towards a tighter monetary policy stance and began to raise interest rates in 1989.

By the following year, interest rates had been increased five times and the stock market began plummeting.

As a result of the bubble bursting, the Japanese economy experienced what is called “the lost decade” as economic growth became one of the lowest of all major developed nations.

The Dot Com Bubble of 1990 – 2000

Despite the recent collapse of the Japanese stock market, the US market had not learned the valuable lesson of overvaluing companies.

The rise of the internet and the rapid adoption fueled a boom in internet-related stocks as investors scrambled to buy anything that had a .com in it.

Between the mid-1990s and the peak in early 2000, investor mania for internet stocks led to a stunning 400% rise in the NASDAQ.

In early 2000, the Federal Reserve announced plans for interest rates to be raised aggressively.

Coupled with subsequent bad news of Japan falling into recession, investors began pulling out of internet stocks.

The stock market began to fall and as investors grew fearful and delved into the fundamentals of the internet companies they realized they were burning a lot of cash with very little if any revenue.

This precipitated further falls, resulting in the collapse of several major internet companies and further panic amongst investors.

By the time the market bottomed in late 2002, the market had dropped 78% from its peak.

Conclusion

Economic bubbles occur infrequently throughout history so they are often ignored by investors when they are being formed.

Despite many instances of economic bubbles forming in the past, investors still keep getting caught up in mass hysteria, and large price collapses.

Developing an understanding of the way economic bubbles are formed can protect investors from their effects.

Despite each economic bubble occurring for different reasons, they share common elements and themes which makes studying them useful.

In all cases, despite different triggers, they follow a similar five-stage process:

Stage 1

Investor expectations begin to divorce themselves from rational analysis and the price of the asset begins to rise above what the fundamentals would reasonably imply would be ‘fair value’.

Stage 2

A very large upswing in prices occurs to unrealistic heights as a result of a self-fulfilling feedback loop.

Stage 3

The bubble pops often in response to some sort of triggering event, such as actions by regulators, an easing in supply constraints, or analysis showing further profits are impossible.

Stage 4

After the bubble pops and prices have already begun falling, investors begin to lock in profits and start selling on masse, resulting in a rush for the exits.

Stage 5

Prices plummet to zero or extreme bargain prices as the asset falls out of favor with investors.

By being aware of the commonalities of past economic bubbles, savvy investors can use the different stages as signposts for impending crashes.

By positioning themselves appropriately to be aggressive as a bubble inflates but then be comfortable to step out of the way at the top as soon as the bubble bursts, investors can enjoy outsized profits from these unique events.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.

Could Bitcoin be in a late stage 2? The democrats are in charge and are exploring ways to regulate and tax bitcoin transactions. Maybe we are in the early stage 3?