Contents

Mark Twain once said “history doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes”.

Once you have been investing in markets for a while, you begin to see patterns emerge that tend to repeat themselves – not exactly like the past however, but they do often ‘rhyme’.

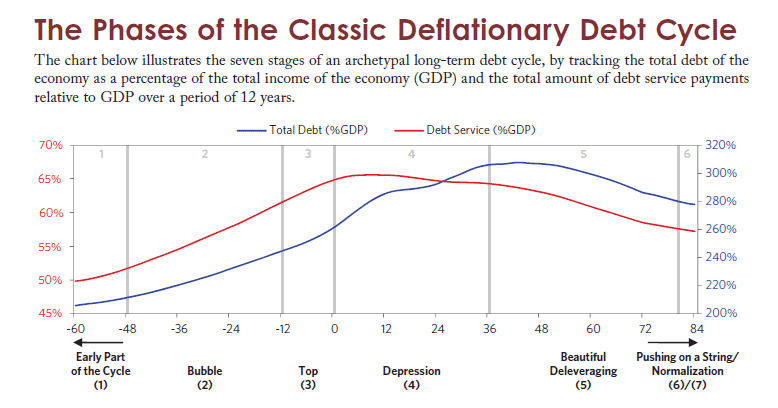

A relatively well-known cycle is Bridgewater’s Debt Cycle Model.

Founder Ray Dalio is famous for drawing investor’s attention to two cycles he’s identified – the short-term debt cycle which lasts between 5 to 8 years and the long-term debt cycle which lasts between 50 to 75 years.

These two debt cycles have repeated themselves many times throughout history, following a very similar pattern because every time someone borrows, they create a cycle.

This occurs because if you borrow money today, it means you will need to one day spend less than you earn so you can pay back the debt, thus creating a cycle.

This is true for both individuals and the economy as a whole.

This process creates an almost mechanical and predictable sequence of events that Dalio has observed many times in the past.

For example, the short-term debt cycle tends to go as follows:

- At the beginning of the cycle, an expansion occurs, and spending increases, resulting in increasing incomes, asset values, and inflation.

- The Central Bank seeks to manage inflation by raising interest rates, making credit more expensive, and thus decreasing borrowing and therefore spending and incomes.

- Economic activity starts to decrease – if this goes too far it can lead to a recession or even a depression if severe enough.

- The Central Bank starts to decrease interest rates to stimulate borrowing, which therefore increases spending and economic activity.

- A new expansion starts and the cycle begins anew.

This pattern happens over and over again, typically lasting between 5-8 years.

However, the economic growth required across each subsequent cycle creates the need for more debt than the cycle before.

Eventually, this leads to the build-up of the long-term debt cycle where the debt levels exceed income growth. Source: Bridgewater Associates

Source: Bridgewater Associates

Across many decades, the debt burden continues to increase and eventually hits a peak, just as it did in the United States with the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, Japan in 1989, and during the Great Depression of 1929.

As the bubble bursts, economic activity slows, borrowing stalls, incomes fall and asset values plummet.

Normally, Central Banks intervene by lowering interest rates but after many short-term debt cycles repeating themselves over the decades, interest rates are already at zero.

This means that the economy cannot be stimulated using traditional measures and a painful, but necessary deleveraging begins such as where the United States finds itself now.

By understanding the basic pattern of the short-term and long-term debt cycles, we can see how it interplays with the demand side of the economy.

The opposite of the demand perspective is the viewpoint of supply, which is the capital market cycle.

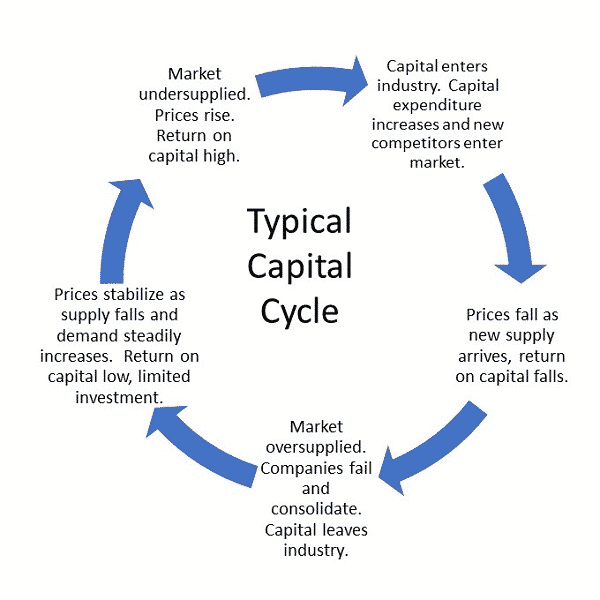

Like the debt cycles, the capital market cycle also has several patterns it repeats and by understanding how it works and what to look out for, we can get a valuable insight into the state of the economy and whether its time to make riskier or more conservative investment allocations.

The Capital Market Cycle

While many investors are familiar with debt cycles due to Ray Dalio’s fantastic work, few are familiar with capital market cycles.

Both the debt cycle and capital market cycles feed off one another so it’s important to understand both, so that you can predict where you are within the cycles and allocate your portfolio assets accordingly.

Recall that as a debt cycle transitions from the bust at the end of the cycle to an expansionary period at the start of the cycle, there is a lowering of interest rates in an effort by Central Banks to stimulate the economy.

The impact of this is that it makes the cost of capital cheaper as investors can borrow money from banks at low rates with very attractive loan conditions.

This leads to a flood of cheap capital entering the system, looking to buy assets or invest in businesses in order to generate a return.

The capital will be seeking to make returns in excess of the cost of capital.

The cost of capital can also be the costs associated with servicing debt from borrowed money from the bank, but it can also be equal to other measures.

For example, other cost of capital measures can be consumer price inflation (which is a defect devaluation of currency) or as part of an investment mandate, such as those made by pension funds so that they can cover the cost of future pension redemptions by members.

In either case, the capital holders are always seeking to make more than it cost them to do nothing with the capital. Source: valuewalk.com

Source: valuewalk.com

As interest rates come down, it directly impacts the returns of some assets, with government bonds and treasuries being notable examples.

As a result, a ‘flight of capital’ begins to form, with capital moving towards riskier investments such as stocks and junk bonds.

In the early stages of the capital market cycle, this influx of new capital pushes up asset prices.

At first, everyone is happy because, on paper, they’ve just become wealthier.

This encourages more capital to be pushed into riskier investments, followed by further rises in asset prices.

Eventually however, the excess capital capacity soaks up all the returns, to the point where further returns above cost of capital are highly unlikely.

At this point, the cycle has peaked and the capital market cycle heads into its downwards phase.

In this phase, capital starts to be withdrawn from further investments and new ventures are not considered.

This can lead to economic contraction (precipitating the start of a new credit cycle) or if managed well and not too disruptive, it can result in the scene being set for a new capital market expansion as the cost of capital rises in response to the lack of capital.

This is why understanding the debt cycle is important for understanding the credit cycle as one can feed the other.

Up until this point, we’ve covered the capital market cycle from a macroeconomic perspective, but it is important to remember that it occurs at a sector and microeconomic level as well – all of which feed into the broader macroeconomic environment.

The following section will walk through a detailed example of the capital market cycle dynamic playing out at a microeconomic level and then touch on the dynamic at a sector level.

The Capital Market Cycle – Example

Understanding how the capital cycle works on a microeconomic level can assist investors in making an informed decision about whether to buy stock in a particular company.

Individual companies can be affected by a capital market cycle on several fronts:

- On the macroeconomic level (such as what was described in the previous section)

- On the industry level (such as Venture Capital and Private Equity funding in ‘hot’ sectors)

- At a company level (As capital can be constrained by investment decisions, company performance and corporate debt ratings affecting borrowing power)

Let’s explore how this could play out for an individual company, against today’s backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, say there was a manufacturer of disposable medical equipment such as face masks, surgical gowns, gloves, etc., called Medico Manufacturing.

For years the company has been able to achieve steady growth and has built a strong reputation amongst investors as being a quality business, with good management and good manufacturing capabilities.

One day a global pandemic occurs, creating a surge in demand for disposable medical equipment, exactly like the type produced by Medico Manufacturing.

With reports of the global pandemic lasting for 18 months or more, the demand for stocks such as Medico Manufacturing goes through the roof – rising 30% in the space of a few weeks.

Soon Medico Manufacturing is approached by a helpful team of investment bankers who sell them a vision of a tidal wave of demand for medical supplies as the global pandemic ravages economies for years to come.

Emboldened by the recent surge in Medico Manufacturing’s stock price and the opportunities presented by the global pandemic, the strategy team at Medico Manufacturing work together with the helpful investment bankers to put together an aggressive growth plan to build multiple manufacturing plants all over the world.

While some members of the Management Board have concerns given Medico Manufacturing has historically been a US-based manufacturing business with a conservative investment style, the surging stock price and potential for even higher rewards from their unvested options lead them to approve the plan.

In order to realize their expansion plan, Medico Manufacturing requires a significant amount of capital which they don’t currently have.

With global interest rates at near-record lows and investor demand for medical stocks at fever pitch, the group of helpful investment bankers convince management that they should do a capital raising.

Medico Manufacturing enlists the help of the investment bankers to put together an attractive prospectus for a secondary share offering and drum up significant support from investors.

With the global macroeconomic capital market cycle near its peak, at the same time as the long term debt cycle moving into the deleveraging phase, interest rates are at zero and government bonds are paying almost nothing.

As a result, investors are chasing returns in a low-return world and are willing to take on more risk than usual to do so.

In this instance, prudent investors ignore the fact that Medico Manufacturing has no experience with offshore manufacturing operations and has never expended outside of its home state in the United States.

They also ignore the risks that the pandemic might fizzle out earlier than 18 months or that a vaccine could be developed very soon.

Against this backdrop, the secondary share offering is heavily oversubscribed and Medico Manufacturing is able to get the capital injection it was seeking.

As an added bonus, news of the expansion plans has attracted the attention of market pundits, which causes the stock price to continue surging ever higher, to a PE ratio almost double the long-term average for the stock.

Meanwhile the investment bankers congratulate themselves on a job well done and walk away pocketing some hefty commissions.

Medico Manufacturing quickly gets to work deploying their newfound capital, acquiring land and building factories in foreign countries with cheap labor costs.

Pretty soon, problems begin to emerge as the management team has to deal with working through problems they don’t have any experience in, such as working with remote teams and operating in jurisdictions with different laws and customs.

Nonetheless, with the aid of some helpful Management Consultants, Medico Manufacturing finally gets production set up and going.

The Finance department begins raising concerns over expenditures, but this is quickly glossed over by the Management Board based on the incredibly large revenue projections from the investment banker’s capital raising prospectus.

Unfortunately for Medico Manufacturing, due to government shutdown and social-distancing promoting actions, the rate of spread of COVID has slowed considerably, such that the number of hospitalizations has fallen dramatically, alongside a drop in demand for medical supplies.

Medico Manufacturing’s offshore facilities operate at well below capacity, making them uneconomical to run.

Pretty soon this starts to weigh on company earnings as revenue growth is far below expense growth.

A year later, Medico Manufacturing’s profits have fallen to anemic levels and the share price has collapsed by 60% as investors constantly withdraw their capital in the face of increasingly poorer returns.

Unfortunately for Medico Manufacturing, profits and the share price continue to dwindle until eventually they face a barrage of stock downgrades by investment banks and brokers.

With little hope of attracting more capital from investors to keep the company afloat, Medico Manufacturing is forced to merge with its rival at a discount to net assets.

The experience of Medico Manufacturing is a prime example of the capital cycle at work.

- In the beginning, there is a consistently profitable business with good returns.

- Investors seeking good returns on their capital are happy to invest in high-return, quality businesses.

- Capital boosts short-term returns and encourages further investment.

- Over-investment occurs and a supply glut is created, causing the business to begin a downturn.

- As returns and business quality falls, capital begins to flee.

- Eventually returns fall below the cost of capital and the business is unable to attract any further capital investment, necessitating a restructure which starts the cycle anew.

Source: Goodreturns.co.nz

Source: Goodreturns.co.nz

As mentioned previously, similar cycles can play out at a sector or industry level.

For example, during the technology bubble of the late ’90s, the telecommunications industry suffered from a bubble in the capital cycle.

Demand was so great that telecommunications companies started to increase fiber-cable infrastructure at a rate that was more than double the rate of actual traffic.

Pretty soon, returns evaporated and there was a flight of capital, leading to many bankruptcies and mergers.

A similar dynamic played out in the housing industry in the lead up to the Global Financial Crisis as the ratio of home prices to income rose to high levels.

As house prices rose, more capital was allocated to it by investors, perpetuating further asset price increases and attracting even more capital.

Like all capital market cycles, eventually it too burst as capital fled the housing market and house prices collapsed up to 40%.

Conclusion

The capital market cycle refers to the dynamic in which the flow and access of capital increases and decreases in a continuous cycle that follows a recurring pattern:

- As an industry, sector, business, or economy prospers, it begins to generate high returns.

- High returns begin to attract capital.

- Rising capital boost short-term returns, increasing investment, and further capital attraction.

- Over-investment occurs leading to a supply glut.

- Future returns are poor and a capital flight takes place.

- Industries/sectors/businesses/economies restructure as returns are below the cost of capital, sowing the seeds for the next expansion.

This cycle occurs at the macroeconomic, sector/industry, and microeconomic levels.

The cycle is complicated by the fact that it can be at different stages at different levels of the economy (e.g. bubble phase on a sector level, but in a downturn at a microeconomic level).

In addition, the capital market cycle also interplays with the debt cycle with one (demand) affecting the other (supply).

By understanding how the capital market cycle works at each level, as well as how it interacts with the debt cycle, investors can learn to spot the signs of over-investment and capital miss-allocation, to avoid the inevitable downturn and bust in the cycle.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.